The jolt of fiery energy I felt when I made the decision to live ferociously with impactful purpose finally zapped the negativity from my long-term outlook.

I had just completed an intense and not particularly encouraging check-in consultation with my medical oncologist before my next-to-last of 16 chemo infusions. It was early August 2015, and I was approaching the halfway point of 10 months of active treatment for Stage 3c infiltrating ductile carcinoma (breast cancer). Lumpectomy surgery and radiation were still on the horizon, but if I could finish chemo, I thought I could literally conquer anything.

Vertigo Amidst Chemo

Two months had passed since I’d experienced a whopper bout of vertigo that had landed me in the emergency room in the middle of the night, and I still had not regained my sense of balance. High heels were absolutely not an option. Not that I felt like wearing dress shoes when I kept my bald head hidden with bandanas or fedoras.

The vertigo episode was likely the result of what I thought was a couple harmless acupuncture treatments for chemo nausea combined with an unusually wet spring in the Denver, Colorado, area that amped up my allergies and created significant inflammation in my inner ears. The terrifying night of endless spinning and throwing up was the closest I have ever come to dying. My panic sparked an out-of-body experience, my first indication that cancer was gearing up to change my life’s trajectory in unimaginable ways.

Mental Health Concerns

As I approached the chemo finish line by early August, I was drained of energy, fed up with perpetually feeling sick, and petrified I might never feel good again. My escalated anxiety levels couldn’t recede because I had become consumed with cancer.

Cancer dictated my every thought, and I was conflicted over whether I could or should stop chemo treatments early. By then I had heard plenty of stories from those who had not completed the prescribed number of chemo treatments, and they had experienced no recurrences. Still, I had a non-aggressive grade of cancer that was behaving aggressively. I was an anomaly because I didn’t fit the staging parameters, which made me feel yet again like a freak who didn’t fit in.

I became concerned with the state of my mental health, the negative thoughts swirling in my mind, and how I was becoming my own worst enemy.

On the sleepless night before my scheduled consult with my medical oncologist and my 15th chemo infusion, I decided to ask her for a referral to a therapist who understood how challenging life with breast cancer was for a Type A businesswoman like me who wanted to believe she was in control but knew she was spiraling out of control.

When I asked my oncologist the next day for a therapist referral she looked puzzled, so I assumed I needed to provide more specific guidance. “Whoever you recommend needs to understand that I am organized, schedule-driven, efficient, and guided by data,” I declared. “I need help.”

She wisely interrupted me before I could transition into full-on panic attack.

“Diane, those in the psychology field typically don’t specialize in an area like cancer.” She shook her head as she spoke, releasing loose black curls that fell across her face which she gently pushed aside with her hand. “In fact, those of us who are on the medical side typically don’t receive much, if any, training on how to work with cancer patients when it comes to their emotions and character traits. I wish we did. By the way, if you do find someone who specializes in working with cancer patients, they likely won’t take your health insurance, if your insurance company even covers mental health services.”

I was astonished by her response. Our medical community continued to make fairly significant progress in the identification and treatment of cancers, but it seemed that little to no attention was being paid to how the disease impacts a person psychologically.

I stopped ranting and calmed down.

“Why is there such a gaping hole in the amount of mental health support provided to cancer patients?” I asked in a pleading, sympathetic voice.

“Because the dollars provided by government funding or private donations typically go to research to find cures for the various types of cancer.”

Although I understood the reasoning for focusing on cures, I didn’t completely agree with the logic. Treatments were, for some types of cancers, becoming more effective and some survivors were living longer, but what type of a life were we living as we slogged through treatment, let alone as we tried to get back to life after treatment ended? Were other survivors as confused as I was about my feelings?

At that catalyzing moment, I realized I needed to finally stop whining and start truly living. And to start truly living, I needed to help create solutions.

During that afternoon’s chemo infusion, a sense of peace came over me as I pondered the possibilities of how I could apply my skills and resources. I was a connected networker, a business writer who had been trained as a print journalist, and an angel investor who understood and had previously helped raise and contributed funds to similar impact-based projects. Given the level of deficiency that seemed to exist in cancer care and its effects on one’s mental health, I knew I could help bring attention and resources to address the inadequacies.

COPE Becomes a Life Raft

Within a week of ringing the bell on my last day of chemo, I attended a planning meeting with representatives from the University of Denver’s Graduate School of Professional Psychology, which offers a highly-sought-after PsyD degree in clinical psychology. During subsequent meetings, I learned about a field of study called psychosocial oncology, which had been introduced in the 1970s. Ironically, training opportunities for clinical psychologists to learn about the field seemed to exist primarily at the post-doctoral level, not at the graduate school level.

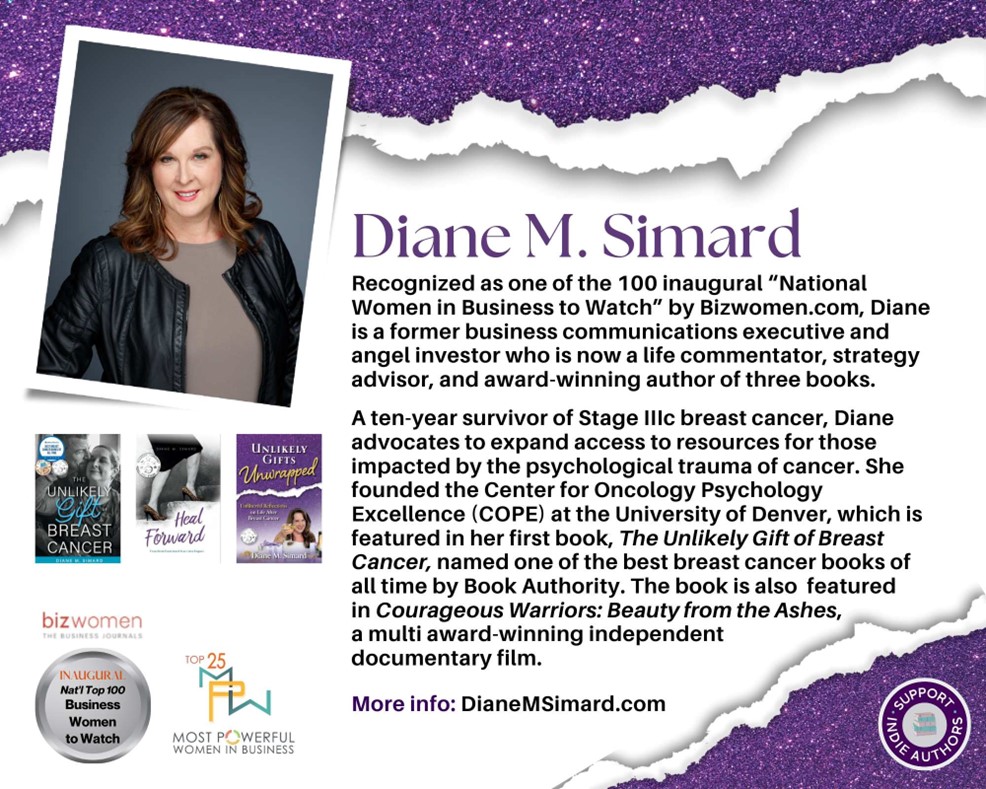

A-ha! More training was needed. Without delay, I decided to seed fund and found a psychosocial oncology specialty at the University of Denver, which we launched less than six months later, the night before my one-year anniversary as a survivor. The specialty was called the Center for Oncology Psychology Excellence, or COPE.

To date, COPE has trained approximately 200 graduate level students how to work with cancer patients. Many of those students are now mental health therapists who help provide support to those who believe, like I do, that a body’s physical ability to heal itself has a great deal to do with the state of one’s mind.

Psycho-oncology Advocacy

I decided to devote my life to advocating for more attention to be paid to the intersection of mental health and cancer by writing books and articles, speaking at cancer-related events, and guesting on podcasts.

Since then, over the course of performing research about why behavioral health counseling services are not considered a standard or required aspect of cancer care, I now understand that our healthcare system will require significant modifications to accommodate those needs. Adjustments will likely include regulation mandates through policy changes, additional training, and additional human resources. And that’s just for starters. Then there is the ultimate question: Who is going to pay for the added costs?

Today, more mental health counselors are providing services, both at care centers and at independent facilities, that specialize in cancer- or health-related trauma. Some of the practitioners take health insurance, while others do not and their services must be paid for out of pocket. Many who were impacted by cancer and received therapy said they benefited greatly from addressing the trauma that can occur before, during, and long after active cancer treatment ends.

The Unlikely Gift of Breast Cancer

In February 2025 I became a 10-year survivor of breast cancer. My resolve to live a life filled with gratitude has never been stronger. In retrospect, while cancer was a miserably unpleasant voyage, it was also a test. An assessment of the strength of my character and the value I place on living.

I use the term “unlikely gift” to describe the impact of my cancer experience. In addition to finally discovering my voice and gaining confidence in myself, the process of researching, writing, and speaking about my experience led me to significant discoveries. For example, I finally made peace with my father over two decades after his death. For over 50 years, I thought I had been the reason he shut me out of his life and had to spend six months in the Veterans Hospital in Lincoln, Nebraska, in the early 1970s due to what my mother called depression. Thanks to research efforts for my first of three books, I discovered he had likely experienced late-onset post-traumatic stress from his experiences in the Korean War 20 years before. PTSD, not me, was the reason he shut me out and remained heavily medicated and aloof the rest of his life.

Writing continues to be an unlikely gift of healing that helps me corral my thoughts and keep the overwhelming experience of breast cancer in perspective. In recognition of my 10th anniversary as a survivor, I will be releasing my next book this spring, titled Unlikely Gifts Unwrapped: Unfiltered Reflections on Life After Breast Cancer, which has already received a five-star rating from Readers’ Favorite. For more information about Unlikely Gifts Unwrapped and my other award-winning books, please go to my website, DianeMSimard.com.

In hindsight, breast cancer created a symbolic transformation in me from victim to advocate. It also helped me achieve the self-acceptance I had searched for a lifetime to find. To those who are experiencing, have experienced, or have been impacted in any way by cancer, you are in my daily prayers. May you initially find comfort, courage, strength, and resolution to so many unknowns. May you eventually also find healing and peace.

Editor’s Note: Get Involved

Cancer doesn’t discriminate. WHATNEXT and its partners are interested in amplifying the voices of those from all identities and backgrounds. If you have a cancer journey to share, reach out here to learn more about how your voice can help spread awareness and inspire individuals from all walks of life.

breast cancer Cancer Mental Health Infiltrating Ductile Carcinoma patient stories patient story Stage 3c Breast Cancer

Last modified: April 11, 2025