Lucas was six years old when his parents were told that he has a very rare and fatal form of brain tumor. His doctor, Dr. Jacques Grill, head of the brain tumor program, vividly recalls the moment he told Lucas’ parents of their son’s fatal illness. Lucas is now thirteen years old and is the only child in the entire world who has been cured of a brainstem glioma. Although it is an exceptionally lethal cancer, the team who attended to Lucas confirm that there is no longer any evidence of the tumor. Lucas and his parents live in Belgium, but he was treated at the Gustave Roussy center in Paris.

Approximately 300 children in the U.S. and 100 children in France are diagnosed with the diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) each year yet this is the only case on record that a child has been completely cured. This week the medical community celebrates International Childhood Cancer Day and especially celebrates statistics showing that eighty-five percent of children who have received a cancer diagnosis will now survive five years or more.

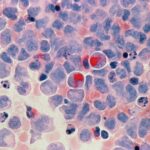

However, that does not hold true for DIPG. The prognosis for these children is especially grim. Most children do not live beyond their diagnosis. Studies have found that about 10% were still alive two years after their diagnosis. Although radiotherapy sometime slows the tumor’s progression, so far there has not been any approved drug that has been effective against the tumor.

Lucas and his parents travelled to France in order for him to join the BIOMEDE clinical trial testing the potential of new drugs for DIPG. Lucas responded well from his very first treatment with a cancer drug called everolimus. He had been randomly assigned to this drug. Dr. Grill told Agence France-Presse (AFP) that he observed the tumor in MRI scans as it gradually disappeared.

Editor’s Note: Get Involved!

Cancer doesn’t discriminate. WHATNEXT and its partners are interested in amplifying the voices of those from all identities and backgrounds. If you have a cancer journey to share, reach out here to learn more about how your voice can help spread awareness and inspire individuals from all walks of life.

Even though the tumor had dissolved, Dr. Grill was hesitant to stop the treatment. He did, however, finally approach Lucas to begin to have him get off the treatment about eighteen months ago only to learn that Lucas had already stopped taking the drug.

Dr. Grill stated that he is not aware of any other case in the entire world that is similar to Lucas’ experience. It is noteworthy that seven other children who participated in the trial were able to survive years after their diagnosis but only the tumor found in Lucas completely vanished.

It is still too early to determine why Lucas fully recovered or how this case could help others in the future. Dr. Grill can only assume that the “biological particularities” of each tumor caused reactions by some children and not by others. He said, however, that the extremely rare nature of the tumor that Lucas carried may possibly have made it more sensitive to the drug.

Offering Hope

The researcher who supervised the lab work, Marie-Anne Debily, said that Lucas’s case offers a tremendous amount of hope. She told AFP that they will attempt to reproduce the differences they found in Lucas’s cells in vitro.

Right now, the team is studying genetic abnormalities found in patients’ tumors. At the same time, they are creating cells called tumor organoids that mimic the progression of the original tissues. Since tumor organoids can retain characteristics of original tumors it makes them unique and in demand as disease models. Lucas’ genetic differences must be reproduced in organoids to determine whether the tumor may be destroyed in its entirety just as it had been to cure Lucas.

Debily said that once that works then they can move on to finding or developing a new drug that affects tumor cells with the result being the same as cellular changes. Although the destruction of Lucas’ tumor generated a lot of hope and excitement, we are reminded that potential treatment remains a long road ahead. Dr. Grill stated that it could take 10-15 years for a drug to be approved. Dr. David Ziegler an oncologist at the Children’s Hospital in Sydne Australia was more optimistic. He stated that the dynamics for DIPG have changed within the past ten years.

Labs have seen many breakthroughs and funding has increased. Dr. Ziegler told AFP that clinical trials similar to BIOMED have convinced him that some patients may be cured sooner than expected.

brain cancer diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma DIPG news

Last modified: February 20, 2024